By Steven Erickson | Press Play October 14, 2014

For the first time in 52 years, the New York Film Festival has expanded to include a 15-film documentary sidebar. This includes the expected portraits of artists (Ethan Hawke’s Seymour: An Introduction, Albert Maysles’ Iris, Les Blank & Gina Leibrecht’s How to Smell a Rose: A Visit with Ricky Leacock in Normandy), but it also encompasses films in which Americans gaze at other cultures and even attempt to critique them (Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Look of Silence, J. P. Sniadecki’s The Iron Ministry, Gabe Polsky’s Red Army.) There’s another strain of documentary here, which might be called the national self-portrait. Arthur Jafa’s Dreams Are Colder Than Death attempts to take the pulse of black America. Ossama Mohammed & Wiam Simav Bedirxan’s Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portraitshows the ravages of civil war in Syria. All these films suggest different ways of making political cinema. Do any of them offer real innovations or ways forward?

It’s not exactly news that sports can be a realm where nationalism plays itself out in a more benign fashion than war, but Red Army examines the last decade of the Cold War through the lens of hockey. Relying heavily on a varied array on archival footage, as well as present-day interviews, he centers on Soviet hockey great Slava Fetisov, who came to prominence in the early ‘80s. Despite a few odd stylistic tics, such as printing interview subjects’ names first in Cyrillic and then in English, Polsky resists the urge to wallow in communist kitsch, like the “North Korea is so cool” tone of several recent documentaries about the hermit kingdom. He’s more concerned with illuminating the differences between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. Fetisov learned to play hockey well, but his training came at the cost of a private life. (Granted, this may be the universal price of fame and success.) When he and his Russian peers were finally allowed to play in the NHL, Red Army doesn’t present this as an unmitigated triumph. While acknowledging the human cost of communism, it also depicts their culture shock, being attacked by North American players and the media, and having difficulty adjusting to a more individualistic playing style. I’m not sure what Fetisov’s exact present-day politics are, but he accepted a post from Putin as Minister of Sport. Now that American-Russian tensions are flaring up again, this reminder of the last Cold War feels more contemporary—and painful—than it might have five years ago: Russia is once again becoming the Other, a convenient source of villains for action movies and TV shows.

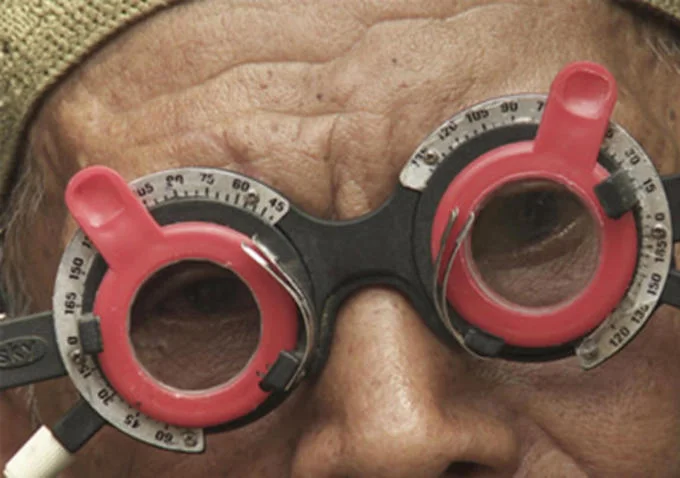

If Red Army offers a relatively mellow look at the damage wrought by the Cold War, the much-awaited The Look of Silence serves up a full, unblinking look at the horrors committed in the name of anti-communism. If it goes down somewhat easier than its abrasive and deeply disturbing companion piece The Act of Killing, in which Oppenheimer had murderers reenact their crimes on film, that’s because it adds some warmth and humanity to the mix—protagonist Adi, an optician, is shown interacting with his family. However, Adi’s elder bother was murdered in the 1965 massacre of a million Indonesian “communists,” and Adi lives in a village alongside his killers, who were never punished and in fact remain free today. The film’s methods are deceptively simple: Oppenheimer shows Adi outtakes from The Act of Killing, which gradually evolve into discussions of his brother’s death, on a video monitor while he watches silently, and then and goes about his daily life, which includes making glasses for the surviving killers from 1965 and interviewing them about the bad old days. Adi seems to be the only Indonesian who wants to remember this period in the country’s history—or, at least, recall it accurately. In some respects, The Look of Silence feels like a response to the critics of The Act of Killing. Violence is never shown, just described, although its full awfulness may exceed what happens in The Act of Killing: several killers describe drinking human blood. People who find Oppenheimer’s films pornographic and exploitative may simply be uncomfortable with an NC-17 reality. But unlike The Act of Killing, The Look of Silence depicts an inspiring level of resistance to historical oblivion.

South Korean director Jung Yoon-suk’s Non-Fiction Diary revolves around a group of serial killers called the Jijon Clan, but it takes in a wide swath of ‘90s Korean history and politics. The Jijon Clan were a gang of six youths who committed a series of horrific murders in 1993 and 1994; their crimes were so surreally awful that when one of their victims described them to the police, they thought she was high on drugs. However, Non-Fiction Diarycontrasts the Clan’s murders, condemned by the whole of Korean society and quickly punished, with the collapses of a bridge and a department store shortly afterwards due to irresponsisble building methods, which actually killed far more people. Relying on period news clips (especially a lengthy talk show debate about the crisis in Korean morality) and interviews with cops, professors and a nun, Jung also lends a stylish touch to the grim proceedings. Non-Fiction Diary begins with still photos, and it then goes into a split-screen montage of some of the images that will follow. The Jijon Clan both hated and envied the wealthy; the first part of their three-line manifesto read “the rich shall be loathed,” yet they wanted to become millionaires. Non-Fiction Diary sees their crimes as an extreme manifestation of the amorality implicit in neo-liberal capitalism. At times, it comes dangerously close to making excuses for them because they weren’t rich, unlike the head of the Sampoong Department Store, whose fall killed more than 500 people. They got capital punishment, he got a slap on the wrist, despite bearing ultimate responsibility for his store’s collapse, as the film points out. However, Jung ultimately offers a range of perspectives on issues like the death penalty, told with a distanced touch, although he sometimes seems to be chafing at the constraints of his film’s form.

The Iron Ministry opens with extreme close-ups of trains as disorienting and immersive as anything in Leviathan, the film that put Harvard’s Sensory Ethnography Lab on the festival map. (Although Sniadecki is a graduate of the Lab, The Iron Ministry isn’t an official product of it.) Shot over three years on trains across China, The Iron Ministry is an experience in flux. Its constant change mirrors that of the economic and social change sweeping the nation it depicts. Sniadecki initially opts for a purely sensual experience; 20 minutes pass before the first subtitle appears. It’s not edited to look seamless—Sniadecki clearly cut together numerous train rides and makes no attempt to smooth over the vehicles’ different looks. Taking a train in China seems a lot like riding on Amtrak 20 years ago, when they routinely over-booked trains and cigarette smoking was still allowed. Yet for every moment of filth Sniadecki shows, there’s an image of beauty or grace to counter it. He also delves into Chinese politics, interviewing passengers on subjects like the role of Islam in Chinese life, pollution and possible progress towards democracy. His presence is subtly but definitely felt. Sniadecki has crafted a film that can stand proudly along the best recent Chinese-made documentaries.

CITIZENFOUR director Laura Poitras was the first journalist to become Edward Snowden’s regular correspondent. (Technically, her film is part of the NYFF’s main slate, not its documentary sidebar.) As an opening card reveals, she was also put on a U.S. government watch list after making her first film and is subject to constant harassment at American airports. I’m sure they’ll be thrilled by her respectful treatment of Snowden here. While the film starts off as a wide-ranging depiction of issues around privacy and surveillance, it settles into a Hong Kong hotel room with Snowden and Glenn Greenwald (then a columnist for The Guardian) for its central hour, which depicts the meeting that led to the public revelations about the NSA’s out-of-control spying. At first, the film seemed strangely impersonal. Poitras uses the first person in on-screen text and reproduces E-mail and chat sessions with Snowden. Yet she never appears in the image herself for more than an instant. I initially thought that a film which dealt more directly with her personal struggles with the U.S. government would bring home the dangers of the NSA’s activities more forcefully. But ultimately, the film she did make, which often resembles an elegantly shot spy thriller, does deliver the justified paranoia of Snowden and Greenwald’s message effectively. It also does a lot to humanize a man who’s too often been demonized as a traitor; the Snowden depicted in CITIZENFOUR is a likable, friendly guy who tried to do the right thing, acted on the fly and got caught up in a world drama that overtook him. Poitras is on his side, certainly, but her depiction is believable.

The relationship of form and content in political cinema has been debated since the late ‘60s, when Cahiers du Cinéma declared all films more conventional than Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Marie Straub’s work reactionary. I don’t want to jump on that bandwagon here, particularly when a film like Kirby Dick’s The Invisible War, although stylistically bland, has managed to accomplish real political goals in changing the way the military prosecutes sexual assault. Nevertheless, there’s something disheartening about the way Non-Fiction Diary conveys an explicitly anti-capitalist message mostly through the usual assemblage of interviews and archival footage, which threatens to collapse into formula.

However, documentaries like The Look of Silence and The Iron Ministryseem to point the way forward. Oppenheimer’s touch in The Look of Silenceis a subtle one; his voice is sometimes heard, and interview subjects occasionally refer to him, often in an unflattering light. Adi is definitely not just a stand-in for Oppenheimer, and he’s a strong enough presence to remind one that The Look of Silence really is a collaboration with Indonesian filmmakers, including a co-director who can only be billed as “Anonymous.” The Iron Ministry is less politically inflammatory than Oppenheimer’s films, but it synthesizes several documentary traditions in an inventive manner. If Americans continue to make films about other cultures - or our own, for that matter - it seems best to leave traces of our own subjectivity in the frame, as The Look of Silence and The Iron Ministrydo, and honestly acknowledge our own perspective’s role in shaping the films we make.

Steven Erickson is a writer and filmmaker based in New York. He has published in newspapers and websites across America, including The Village Voice, Gay City News, The Atlantic, Salon, indieWIRE, The Nashville Scene, Studio Daily and many others. His most recent film is the 2009 shortSquawk.

Originally published in Indiewire Blog, October 14, 2014 -> http://blogs.indiewire.com/pressplay/nyff-documentaries-political-cinema-horizons-from-red-army-to-citizenfour-20141014